KEY FINDINGS: Throughout the world, support for the institution of the family is strong. In every country examined except Sweden, men and women agree that a child needs a mother and father to grow up happily. In all 29 countries, a majority of adults believes marriage is still relevant and that an additional emphasis on family life would be a good thing. Nevertheless, support for marital permanence is weaker, with adults in many countries taking a relatively permissive stance toward divorce.

Marriage is a near-universal institution around the globe. The meaning of marriage, however, varies from country to country and has changed across time. In many places around the world, marriage has become about love and companionship—a stark contrast to pre-Industrial Revolution marriages that were to a large degree about economic survival. Still, marriage continues to be viewed by many as the “gold standard” in relationships, as the optimal arrangement for childrearing, and as a relationship that should not easily be terminated. Precisely how many hold these views around the world is not clear.

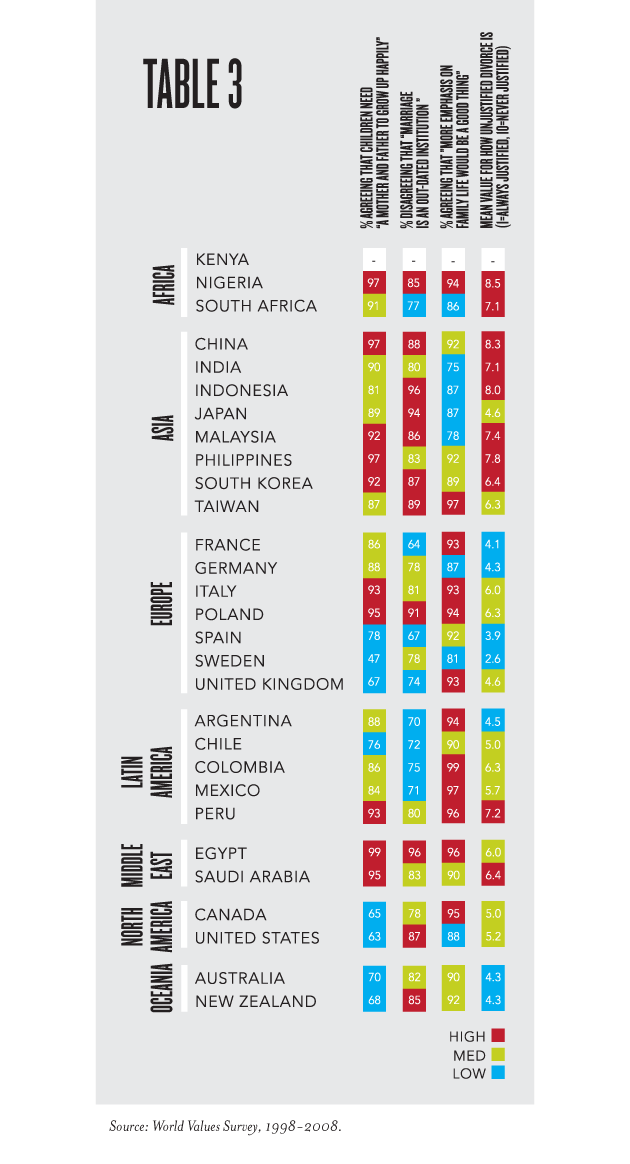

To shed light on adults’ attitudes toward marriage and family life around the world, we present data from the World Values Survey, collected between 1999 and 2007, on four cultural indicators in 29 countries: (1) agreement that a child needs a home with a mother and father to grow up happily, (2) disagreement that marriage is an outdated institution, (3) agreement that more societal emphasis on family life would be a good thing, and (4) opinions about how justified divorce is. Because the World Values Survey has been collected since the early 1980s in many of the 29 countries of interest, we are also able to paint a portrait of changes in family culture over the last 25 years or so.

DO CHILDREN NEED A MOTHER AND FATHER?

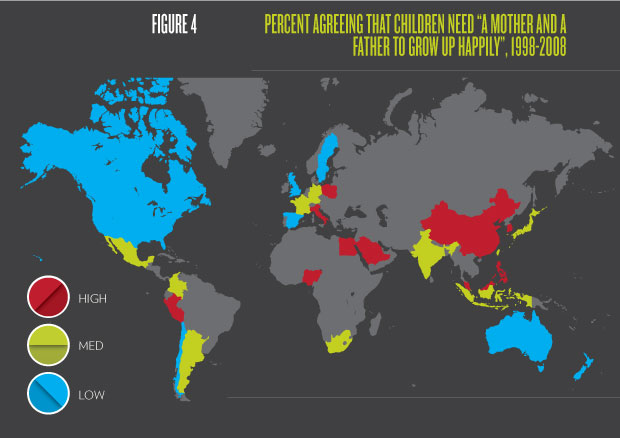

The vast majority of adults around the world believe a child needs to be raised in a home with both a mother and a father in order to grow up happily (see Table 3 and Figure 4). This sentiment is strong in South America; more than 75 percent of adults in Argentina (88 percent), Chile (76 percent), Colombia (86 percent), and Peru (93 percent) believe a two-parent home is necessary for a happy childhood. North Americans are less likely to agree to this idea, but still 63 percent of U.S. adults and 65 percent of Canadians affirm the mother-father household as optimal for raising happy children.

Agreement with the mother-father family ideal is even stronger in Europe than in the Americas, with the sole exception of Sweden. There, only 47 percent of adults agree that a child needs to be raised by a mother and father to be happy. Notably, Sweden is the only country in the world where a minority agrees with this sentiment. Agreement with a mother-father ideal exceeds 90 percent in Italy (93 percent) and Poland (95 percent) and 80 percent in France (86 percent) and Germany (88 percent). More than three-quarters (78 percent) of Spaniards view this family arrangement as best for children, as do two-thirds (67 percent) of British adults.

Support for the mother-father family type is nearly unanimous in the Middle Eastern and African countries: Egypt (99 percent), Saudi Arabia (95 percent), Nigeria (97 percent), and South Africa (91 percent). Asian support for children being raised by a mother and father is also strong. Most of the Asian countries profiled exceed 90 percent agreement: China (97 percent), India (90 percent), Malaysia (92 percent), Philippines (97 percent), and South Korea (92 percent); and the remainder exceed 80 percent: Indonesia (81 percent), Japan (89 percent), and Taiwan (87 percent). Australians (70 percent) and New Zealanders (68 percent) express less agreement, resembling Americans, Canadians, and British attitudes on this issue.

There is not clear evidence that this attitude is changing drastically over time in one particular direction.

FOR MORE INFORMATION VISIT: www.sustaindemographicdividend.org/e-ppendix.

In most cases, support for a mother-father family type has remained relatively stable, or has fluctuated in a nonlinear fashion. Two notable exceptions to this are Chile, which saw agreement with this statement drop from 93 percent in 1990 to 76 percent in 2006; and Sweden, which fell from 71 percent agreement in 1982 to 47 percent in 2006. South African support for the mother- father family ideal may have even grown from 83 percent in 1982 to 91 percent in 2006.

MARRIAGE AN OUTDATED INSTITUTION?

Like agreement that children need a mother and father to be happy, the overwhelming majority of adults around the world disagree that marriage is outdated (see Table 3). In none of the 29 countries did fewer than 64 percent of adults (France) feel this way. Between 70 and 80 percent of adults in most American countries disagree marriage is outdated: Argentina (70 percent), Canada (78 percent), Chile (72 percent), Colombia (75 percent), Mexico (71 percent), and Peru (80 percent). The United States stands out a bit from its neighbors, with 87 percent disagreeing marriage is outdated.

European support for marriage as a relevant institution is similarly strong in most countries. French (64 percent) and Spanish (67 percent) adults are the least likely to disagree marriage is outdated, but support for marriage as an institution exceeds 70 percent in Germany (78 percent), Sweden (78 percent), and the United Kingdom (74 percent). More than 80 percent believe marriage remains relevant in Italy (81 percent), and support for marriage surpasses 90 percent in Poland (91 percent).

Belief in marriage’s relevance is even stronger—these data suggest—in most other parts of the world. The two Middle Eastern countries examined here exhibit strong support for the institution of marriage: Egypt (96 percent) and Saudi Arabia (83 percent). In Africa, 85 percent of Nigerians believe marriage is not outdated; a relatively low (but still high in absolute terms) percentage of South Africans (77 percent) feel the same way. Marriage receives high levels of support throughout Asia and Oceania as well: China (88 percent), India (80 percent), Indonesia (96 percent), Japan (94 percent), Malaysia (86 percent), Philippines (83 percent), South Korea (87 percent), Taiwan (89 percent), Australia (82 percent), and New Zealand (85 percent).

There is some evidence of a decline in this attitude around the world, though it is clearly not universal and not precipitous. Double-digit declines in support for marriage occurred in Chile from 1990 to 2006 (85 percent to 72 percent), in Mexico from 1981 to 2005 (81 percent to 71 percent), in Great Britain from 1981 to 1999 (86 percent to 74 percent), and in India from 1990 to 2006 (95 percent to 80 percent).

FOR MORE INFORMATION VISIT: www.sustaindemographicdividend.org/e-ppendix.

Double-digit increases, however, took place in Japan (76 percent to 94 percent). Still, decline in support for marriage seems to be the more common trend, as modest declines in support for the institution can be seen in many of the other countries examined here.

MORE EMPHASIS ON FAMILY LIFE A GOOD THING?

Around the world, adults overwhelmingly believe that family life deserves more emphasis (Table 3). When asked whether more emphasis on family life would be a good thing, a bad thing, or something they wouldn’t mind, vast majorities report that this would be a good thing. In most countries in the Americas, 90 percent or more believe additional emphasis on family life would be a good thing: Argentina (94 percent), Canada (95 percent), Chile (90 percent), Colombia (99 percent), Mexico (97 percent), and Peru (96 percent). Desire for more emphasis on family is 88 percent in the United States.

European desire for a greater focus on family life is also strong. Swedes are the least likely Europeans to report such a development would be a good thing, but even 81 percent of Swedish adults believe it would be good. Additional family emphasis would clearly be welcomed by most in France (93 percent), Germany (87 percent), Great Britain (93 percent), Italy (93 percent), Poland (94 percent), and Spain (92 percent).

Throughout the Middle East [Egypt (96 percent) and Saudi Arabia (90 percent)] and Africa [Nigeria (94 percent) and South Africa (86 percent)], adults view positively an added emphasis on family life. Asians would also welcome this added focus, although India (75 percent) and Malaysia (78 percent) less so than other countries [China (92 percent), Indonesia (87 percent), Japan (87 percent), Philippines (92 percent), South Korea (89 percent), and Taiwan (97 percent)]. In Oceania, too, a heightened focus on family life would be embraced by most [Australia (90 percent) and New Zealand (92 percent)].

If anything, the desire for added emphasis on family life appears to be growing around the world. Relatively large increases in this attitude can be seen in Mexico (9 percentage points from 1981 to 2005), Great Britain (9 percentage points from 1981 to 2006), Spain (8 percentage points from 1981 to 2007), China (18 percentage points from 1990 to 2007), and Japan (7 percentage points from 1981 to 2005).

FOR MORE INFORMATION VISIT: www.sustaindemographicdividend.org/e-ppendix.

Some countries have witnessed declines in this sentiment, however, including Chile (7 percentage points from 1990 to 2006) and the United States (7 percentage points from 1982 to 2006).

DIVORCE ATTITUDES

While support for mother-father families, marriage, and family life in general is strong around the world, attitudes toward divorce vary widely by region (see Table 3). On a scale of 1 to 10, with 1 being permissive and 10 being restrictive, countries range from the very permissive (Sweden, 2.6) to the very restrictive (Nigeria, 8.5). In the Americas, the countries with the most conservative attitudes about divorce are Peru (7.2) and Colombia (6.3). All other American countries fall below the scale midpoint of 5.5: Argentina (4.5), Canada (5.1), Chile (5.0), Mexico (5.7), and the United States (5.2).

The European countries range from moderate to permissive in their divorce attitudes, with Poland (6.3) and Italy (6.0) being the most restrictive. Swedish adults (2.6) believe divorce is almost always justifiable. Spain (3.9), France (4.1), Germany (4.3), and Great Britain (4.6) are also quite permissive.

The Middle East, Africa, and Asia have the most conservative attitudes toward divorce, though even here the numbers are not always extreme. Egypt (6.0) and Saudi Arabia (6.4) are fairly moderate in their stance on divorce. Nigeria (8.5) is the most conservative nation on this attitude, and South Africa (7.1) is also relatively restrictive. Asian countries vary somewhat widely in their attitudes, ranging from Japan at 4.6 to China at 8.3. In between these extremes are moderate countries like South Korea (6.4) and Taiwan (6.3), and somewhat more conservative countries like India (7.1), Indonesia (8.0), Malaysia (7.4), and the Philippines (7.8).

Oceania, like Europe, is fairly permissive when it comes to divorce. Both Australia and New Zealand have average scores of 4.3, indicating divorce is justifiable more often than not.

There is a clear pattern of liberalization of divorce attitudes in the Americas, Europe, and Oceania. With the exceptions of Colombia, Peru, and Italy, countries in these regions have become more permissive in their divorce attitudes.

FOR MORE INFORMATION VISIT: www.sustaindemographicdividend.org/e-ppendix.

We do not have longitudinal data for the Middle East, but in Nigeria divorce attitudes appear to have become more conservative, and attitudes have been generally consistent across time in South Africa. China has seen attitudes become more restrictive—especially since 1995—but other Asian countries, specifically India, Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan, have become more permissive in their attitudes about divorce. So too have Australia and New Zealand.

CONCLUSIONS

Taken together, these findings suggest that in most countries around the world, adults have relatively traditional family attitudes. They believe children need to be raised by a mother and father to grow up happily. They endorse marriage as an institution, and they wish that there were more emphasis placed on family life. Nevertheless, they hold relatively permissive attitudes toward divorce. This suggests that in many places around the world, adults are wrestling with the meaning of marriage and what an ideal family should look like. On the one hand, they value the institution and its childrearing benefits; on the other hand, they are more open to an individualistic understanding of marriage that allows for the termination of the relationship under many circumstances.

While these are the dominant patterns, there are clearly variations in family culture around the world. North America, Oceania, and Scandinavia generally take a more laissez-faire view of family matters, whereas Africa, Asia, the Middle East, and Latin America embrace a more familistic view of things. These differences can be attributed to variations in religiosity, economic development, political culture, and the relative importance of community vis-à-vis the individual in these different regions of the world.

PRINT THE PAGE