A turning point has occurred in the life of the human race. The sustainability of humankind’s oldest institution, the family—the fount of fertility, nurturance, and human capital—is now an open question. On current trends, we face a world of rapidly aging and declining populations, of few children—many of them without the benefit of siblings and a stable, two-parent home—of lonely seniors living on meager public support, of cultural and economic stagnation.

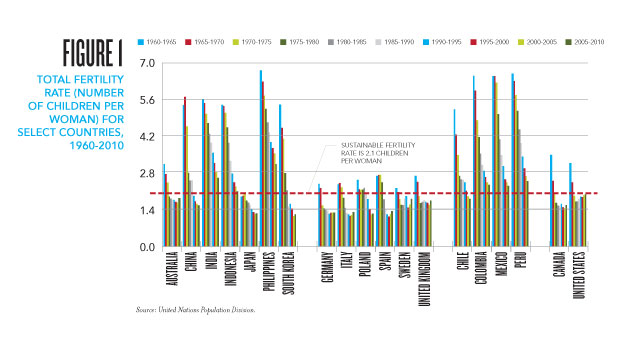

In almost every developed country, including most in Europe and East Asia and many in the Americas— from Canada to Chile—birth rates have fallen below the levels needed to avoid rapid population aging and decline (see Figure 1). The average woman in a developed country now bears just 1.66 children over her lifetime, which is about 21 percent below the level needed to sustain the population over time (2.1 children per woman).1 Accordingly, the number of children age 0–14 is 60.6 million less in the developed world today than it was in 1965.2 Primarily because of their dearth of children, developed countries face shrinking workforces even as they must meet the challenge of supporting rapidly growing elderly populations.

In recent years, the phenomenon of subreplacement fertility has spread to many less developed countries. In fact, the number of lifetime births per woman shrank in a single generation from six or more to less than two in places ranging from Iran, Lebanon, and Tunisia to Chile, Cuba, Trinidad, Thailand, China, Taiwan, and South Korea.3

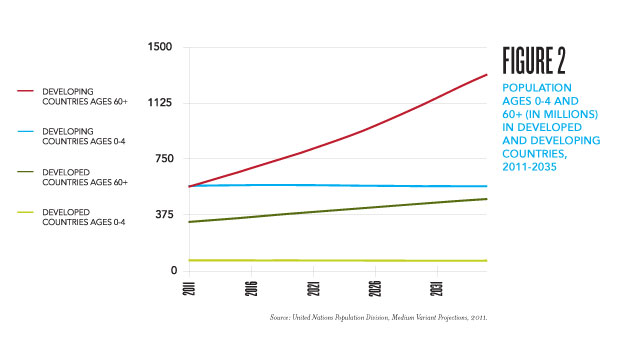

World population is still growing, to be sure; the United Nations projects that our numbers could increase from 7 to 10 billion over the next 90 years.4 But this is a different kind of growth than we have ever seen before. Until quite recently, population growth came primarily from increases in the numbers of young people.

But over the next 40 years, according to the U.N.’s latest “medium variant” projections, 53 percent of world population growth will come from increases in the numbers of people over 60, while only 7 percent will come from people under 30. Indeed, the U.N. projects that by 2025, the population of children under 5, already in decline in most developed nations, will be falling globally as well (see Figure 2).5 This means that world population could well start falling by the turn of the century, especially if birth rates do not break their downward trend.

Accompanying the global megatrend of falling birth rates is a radical change in the circumstances in which many children are raised, as country after country has seen a surge of divorce and/or out-of- wedlock births and a sharp drop in the percentage of children living with both of their married parents. In much of Europe and the Americas, from the United Kingdom to the United States, from Mexico to Sweden, out-of-wedlock births are the “new normal,” with 40 percent or more of all children born without married parents (see Figure 3). Though many of these births are to cohabiting couples, families headed by cohabiting couples are significantly less stable than those headed by married couples. This means that children born outside of marriage are markedly more likely to be exposed to a revolving cast of caretakers and to spells of single parenthood, compared to children born to married couples.

Take the United States. Fully 41 percent of U.S. children are now born outside of marriage. About half of these children are born to cohabiting couples, and about half of them are born to single mothers.6 Both of these groups are much more likely to be exposed to instability (when a parent leaves the household, or a new social parent arrives in the household—both of which are often stressful for children) and spells of single parenthood than are children born to married parents. One study of U.S. children found that 17 percent of those born to married couples, 57 percent born to single mothers, and 63 percent born to cohabiting parents experienced some type of instability in the first six years of their lives.7 Another study found that the percentage of children in single-parent families in the United States more than doubled from 12 percent in 1970 to 25 percent in 2009.8

Or take Sweden, where 55 percent of children are born outside of marriage. The vast majority of these children are born to cohabiting couples. But even in Sweden, where cohabitation enjoys widespread acceptance and legal support, cohabiting families are less stable than married families. One recent study found that children born to cohabiting couples were 75 percent more likely than children born to married couples to see their parents break up by age 15.9 And the percentage of single-parent households with children in Sweden has almost doubled in the last twenty-five years, from 11 percent in 1985 to 19 percent in 2008.10

An abundant social-science literature, as well as common sense, supports the claim that children are more likely to flourish, and to become productive adults, when they are raised in stable, married-couple households. We know, for example, that children in the United States who are raised outside of an intact, married home are two to three times more likely to suffer from social and psychological problems, such as delinquency, depression, and dropping out of high school. They are also markedly less likely to attend college and be stably employed as young adults.11 Sociologist Paul Amato estimates that if the United States enjoyed the same level of family stability today as it did in 1960, the nation would have 750,000 fewer children repeating grades, 1.2 million fewer school suspensions, approximately 500,000 fewer acts of teenage delinquency, about 600,000 fewer kids receiving therapy, and approximately 70,000 fewer suicide attempts every year.12 In Sweden, even after adjusting for confounding factors, children living in single-parent families are at least 50 percent more likely to suffer from psychological problems, to be addicted to drugs or alcohol, to attempt suicide, or to commit suicide than are children in two-parent families.13

And so it is not just the quantity of children that is in decline in more and more regions of the world but also the quality of their family lives, calling into question the sustainability of the human family. Sustainable families don’t just reproduce themselves; they also raise the next generation with the requisite virtues and human capital to flourish as adult citizens, employees, and consumers. And families headed by intact, married couples are the ones most likely to succeed in raising the next generation.

What are the causes and consequences, especially economic, of these recent declines in fertility and marriage? What is the appropriate response of policy makers, business leaders, civil society, and individuals? These questions were addressed at the “Whither the Child?” academic conference sponsored by the Social Trends Institute in Barcelona, Spain, in 2010.

→ FOR MORE INFORMATION VISIT:

www.socialtrendsinstitute.org/Activites/Family/Whither-the-Child.axd.

This report surveys the evidence from that conference, and other relevant scholarship, in an attempt to understand the rapid demographic evolution of modern societies and to suggest options for ensuring their sustainability.

THE FUTURE OF U.S. FERTILITY

by Samuel Sturgeon

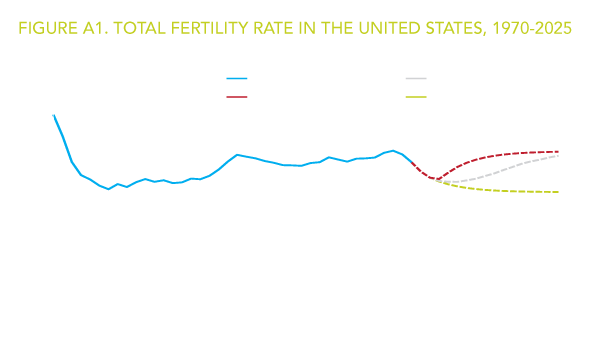

Although fertility in most developed countries has fallen well below the replacement level Total Fertility Rate (TFR) of 2.1 children per woman, the United States is clearly an outlier. For most of the last forty years, the total fertility rate in the United States has hovered slightly below the replacement level TFR. During this time, about 25 percent of the change in the TFR from one year to the next can be attributed to changes in the economy. Because of the Great Recession’s ongoing fallout, the TFR in the U.S. is expected to remain below 2.0 for the next few years. Looking forward fifteen years, Figure A1 projects what the TFR in the United States might look like under three separate economic scenarios:1 a quick economic recovery, a slow economic recovery, and no economic recovery.

One reason that U.S. fertility has remained and is likely to remain comparatively high is that Americans continue to value relatively large families, at least by the standards of the developed world. Specifically, over the last forty years there has been very little change in what most Americans of childbearing age (18–46) consider to be the ideal family size.2 Around three quarters of American adults this age believe that two or three children is the ideal. The average reported ideal family size over the last forty years has remained fairly constant, hovering around 2.5 children with a high of 2.73 in 1970–74 and a low of 2.39 in 1995–99 (see Figure A2). In 2010, the ideal family size was 2.66 for American adults age 18-46. These cultural trends suggest that U.S. fertility will return to replacement levels when the economy recovers and Americans feel freer to afford their fertility ideals.

1 The three projections are based on models using the following hypothetical economic patterns: Quick recovery: The unemployment rate drops to 5.0 by 2012 and remains there through 2015. Consumer Sentiment Index rises above 100 by 2012 and remains above 100 through the end of 2025. Slow recovery: The unemployment decreases by .5 of a percentage point per year until 2019 when it reaches 5.0 and remains at 5.0 through 2025. Consumer Sentiment Index experiences a similar slow rise before reaching 100 in 2020. No recovery: The unemployment rate remains at 9.0 through 2025 and Consumer Sentiment Index remains in the low 70s.

2 Kellie J. Hagewen and S. Philip Morgan, “Intended and Ideal Family Size in the United States, 1970–2002,” Population and Development Review 31 (2005): 507–527.

CAUSES OF FALLING FERTILITY AND MARRIAGE RATES

Urbanization is a key driver in the transformation of global demographics. Today, more than half the world population lives in urban areas, up from 29 percent in 1950.14

This trend impacts human reproductive behavior. For city dwellers, whether rich or poor, the economics of childbearing are challenging. In the not-so-distant past, when the majority of the world’s population were still small-scale farmers, most children could still play economically useful roles. They could tend to fields and farm animals, deliver messages between fields and home, and perform tasks in the home that have now been largely supplanted by the widespread consumption of store-bought food and clothing and the introduction of modern appliances. In an urban environment, however, children are no longer an economic asset to the parents but an expensive (and easily avoidable or deferrable) economic liability.15

Declining real wages and increasingly insecure job tenure have also no doubt played a big role in many young couples’ conclusions that they should either remain childless or delay marrying and starting families. In a paper presented at the Social Trends Institute conference, demographers Wolfgang Lutz, Stuart Basten, and Erich Striessnig noted that over the last generation in the developed world, especially in Europe, entry into professional life after education has become more difficult. “In many European countries,” they observed, “where young employees in the past enjoyed positions which were more or less permanent, today many have to jump from one short-term contract to the next. Under such conditions it becomes less attractive to establish a family and, subsequently, to avoid dedicating all of one’s time and energy to pursuing a professional career.”16

THE FUTURE OF NONMARITAL CHILDBEARING IN THE U.S.

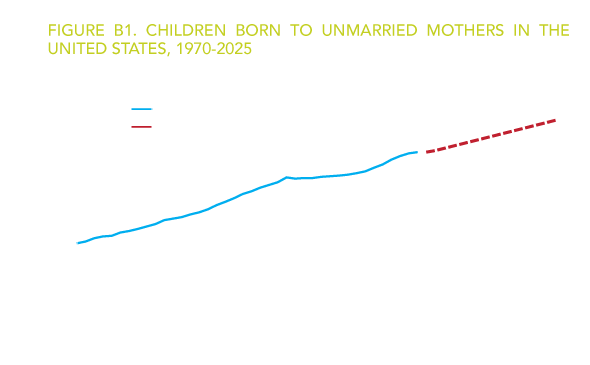

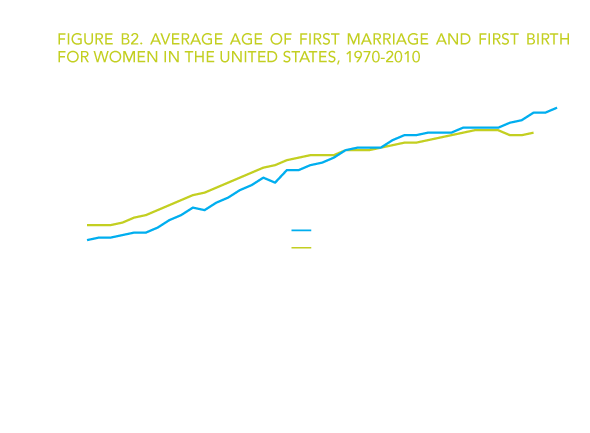

Over the course of the last forty years, nonmarital childbearing in the United States has grown in almost linear fashion. These trends are likely to continue in the near future (see Figure B1). One reason that the percent of children born to an unmarried mother is likely to rise is that the average age at first marriage is outpacing the average age at first birth (see Figure B2).3 This means that a growing percentage of women in the U.S. are marrying after, not before, they have children.

Since 1970, the average age at first marriage rose by more than five years, while the average age at first birth rose by less than four years. As a result, beginning in the early 1990s, the average age at first birth was younger than the average age at first marriage. The differential rate of increase between these two trends partially explains the rise in the percent of children born to unmarried mothers. For example, in 2008, 40.6 percent of all births were to unmarried mothers; however, the figure for first births was 48 percent.4 Figure B1 contains an estimate of what the percent of children born to unmarried mothers might look like through 2025 if the average age at first birth and average age at first marriage continue to increase at the same rate they have for the past forty years. According to this model, sometime around 2023 half of all children born in the United States will be born to an unmarried mother.

3 The U.S. Census Bureau calculates the median age at first marriage as part of the Current Population Survey. The median age at first marriage for the years 1970–2010 are taken from the following table: http://www.census.gov/population/socdemo/hh-fam/ms2.pdf. The mean age of mother at first birth for the years 1970–2008 comes from the National Vital Statistics Reports published by the National Center for Health Statistics.

4 Derived by Demographic Intelligence from the National Vital Statistics System.

Meanwhile, the increasing demand for education in modern, urban economies also discourages fertility. In today’s advanced societies, a college degree has become for most people a prerequisite for achieving a living wage, and many people have not completed their schooling before their own or their spouse’s biological fertility is already in decline. Even if a young couple nonetheless succeeds in starting a family, the same upward trends in the cost and duration of education will leave them scrambling to figure out how they can ever afford to endow their children with the minimum education required to succeed in 21st-century job markets.

Finally, although social-security systems around the world, as well as private pension plans, depend critically on the human capital created by parents, they paradoxically provide incentives to remain childless or to limit family size. In advanced economies, citizens no longer must have children and raise them successfully in order to secure support in old age. Instead, the elderly in developed countries have largely been able to rely on health and retirement benefits paid for by other people’s children: that is, working-age adults who are currently paying taxes for public pensions.17

THE FUTURE OF CHILEAN FERTILITY

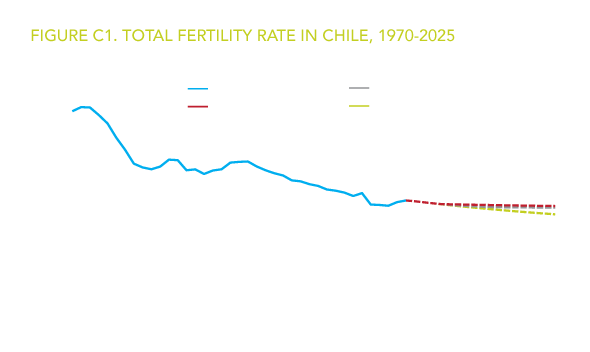

The total fertility rate (TFR) in Chile has fallen markedly over the last forty years, from 3.4 to 1.9 children per woman over this time period (see Figure C1).5 Part of the decline is due to increased development and urbanization, which make children more expensive.6 Other possible factors include declines in religious participation and the influence of the Catholic Church,7 increases in expressive individualism, as well as increases in women’s labor force participation, and the difficulty that some Chilean woman have in combining work and family.8 Because of these larger trends, yearly fluctuations in the economy do not appear to play as strong a role in the TFR in Chile as they do in the United States; however, economic conditions still seem to have an impact. Figure C1 projects what the TFR in Chile might look like under three separate economic recovery scenarios in light of the recent global economic downturn: quick economic recovery, slow economic recovery, and no economic recovery.9

5 The total fertility rate for the years 1970–2008 come from Jorge Rodríguez Vignoli and Mariachiara di Cesare, “Reproducción adolescente y desigualdades en Chile: tendencias, determinantes y opciones de política,” Revista de Sociología 23 (2010): 39–65.

6 John Bryant, “Theories of Fertility Decline and the Evidence from Development Indicators,” Population and Development Review 33 (2007): 101–127.

7 Carla Lehman Scassi-Buffa, “Chile: ¿Un País Católico?,” Centro de Estudios Publicos: Puntos de Referencia No. 249 (2001).

8 Lin Lean Lim, “Female Labour-Force Participation,” in Completing the Fertility Transition, Population Bulletin of the United Nations, Special Issue Nos. 48/49 (2009): 195–212.

9 TFR was modeled by using the annual unemployment rate taken from the World Bank database for the years 1981–2008. http://data.worldbank.org/country. The hypothetical economic patterns in the three different scenarios are similar to those used to predict the TFR in the United States in Figure A1.

Samuel Sturgeon, Ph.D., is director of research for Demographic Intelligence, which provides U.S. fertility forecasts and demographic analysis to companies in the juvenile products, household products, and pharmaceutical industries.

THE ROLE OF CULTURE

Changing values and conceptions of the good life have also played a role in driving down rates of marriage and childbearing. The initial emergence of subreplacement fertility in Scandinavia, and its subsequent spread throughout Western Europe, for example, was strongly associated with the diffusion of secular values, the decline of religious authority, and the rise of expressive individualism. Demographer Ron Lesthaeghe and his colleagues have gathered extensive data on the values revolution among the young that swept though Europe starting in the late 1960s. They looked at changing attitudes toward divorce, contraception, sex, single parenthood, and organized religion and noticed a clear geographical pattern. Attitudes once termed “counter-cultural,” and today associated with mainstream secular liberalism in Europe, first gained prominence in Scandinavia in the late 1960s. They then spread south, eventually diffusing though Spain, Portugal, Italy, and Greece by the later part of the 1970s and through the 1980s. And as these attitudes spread, birth and marriage rates fell almost in lockstep.18

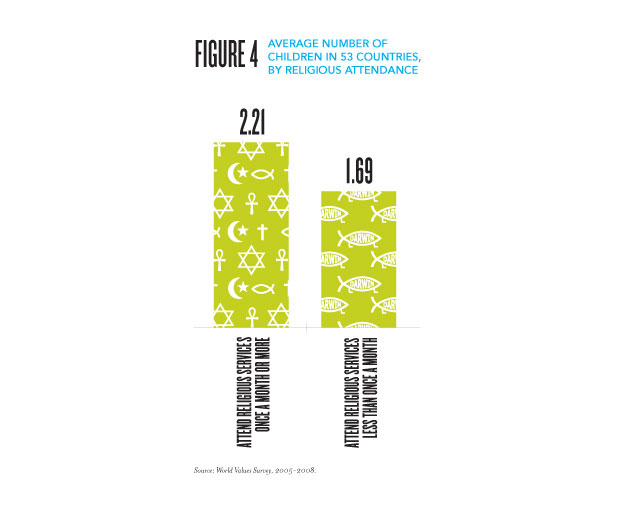

Today there remains within the individual countries of Europe, and of the West generally, a strong and growing correlation between conservative religious values and larger-than-average family size. In France, for instance, practicing religious white women have a half-child fertility advantage over nonreligious white women and, as political scientist Eric Kaufman has pointed out, this disparity has been increasing over time.19 In Spain, women who are practicing Catholics have significantly more children than do nonpracticing Catholic women—holding income, marital status, education, and other factors constant.20 Much the same story can be found throughout the globe, where the religiously observant typically have markedly higher birth rates than does the rest of the population. Our analysis of 53 countries from every region of the world, from Africa to Oceania, and from the Americas to Europe and the Middle East, indicates that men and women who attend religious services monthly or more have had about .5 more children on average than their peers who attend services less often or not at all (see Figure 4).21

Another powerful factor appears to be the expanding influence of television and other cultural media. Even in the remotest corners of the globe, when television is introduced, birth rates soon fall. This is particularly easy to see in Brazil. There television was not introduced all at once but rather province by province, and thus it is possible to see after the fact that every place the boob tube arrived next, birth rates plummeted. Today, the number of hours a Brazilian woman spends watching domestically produced telenovelas strongly predicts how many children she will have.22 These soap operas, though rarely addressing reproductive issues directly, typically depict wealthy individuals living the high life in big cities. The men are dashing, lustful, power-hungry, and unattached. The women are lithesome, manipulative, independent, and in control of their own bodies. The few characters who have young children delegate their care to nannies.

The telenovelas, in other words, reinforce a cultural message that is conveyed as well by many Hollywood films and other North American and European cultural exports: people who are wealthy, sophisticated, free, and self-fulfilled are those people who have at most one or two children and who do not let their parental roles dominate their exciting lives.

Before concluding, however, that modernity necessarily fosters sterility, one should note a still small but possibly important countertrend. In recent years, birth rates have begun to rise modestly in places that have strongly committed to gender equality and that have large shares of women in the formal labor force, such as Sweden and France.

By contrast, fertility is today lowest in nations where traditional family and religious values are still comparatively strong but on the wane, such as South Korea, Japan, Italy, and Greece. And this pattern may partly reflect differences in how well conflict over evolving gender roles has been resolved. According to cultural observers in South Korea, for example, Confucian values remain strong enough to inhibit out-of-wedlock births, of which there were a mere 7,774 in 2007.23 Yet birth rates are very low, and divorce is comparatively high.24 The common explanation is that women still feel social pressure, if they marry, to show exceptional deference to their husbands and mothers-in-law. For the new generation of South Korean women, who now have many opportunities to support themselves without marrying, this looks like a bad bargain. Thus many remain single, get divorced, or limit their fertility.

Looking at the modestly higher fertility found in at least some countries that have large numbers of working women, some observers have proclaimed that “feminism is the new natalism” and have called for more measures to boost gender equality and state support for working women as a way to sustain population.25 The premise of this argument, however, is easily overstated. Whether the pattern really applies to the world as a whole, for example, is disputed by demographers.26 Moreover, the comparatively higher annual birth rates of such “feminist” countries as Sweden or France partly reflect the temporary effect of more women having their first child at later ages, as well as a surge in out-of-wedlock births and the comparatively high fertility of their immigrant populations.27

ECONOMIC CONSEQUENCES OF THE NEW GLOBAL DEMOGRAPHICS

What is the relationship between population growth and economic growth? Does fewer people mean there is more for each to enjoy? Or that each will have to work harder?

With the benefit of hindsight, it is not hard to see the role population growth has played over time in fueling economic growth and the emergence of affluent societies. Greater numbers often meant greater economies of scale, through assembly lines and other means of mass production, and they also allowed for more specialization of labor.28 More people also means a larger workforce for businesses and, crucially, more demand for the products they sell. Population growth can also be a spur to innovation, as it causes people to look for more efficient ways to grow food, for example, or to find substitutes for depleted natural resources like whale oil and firewood. The more brains are available to work on natural- resource challenges, the sooner someone will come up with the idea that provides a solution. The more general point is that people can be resources for, rather than drains on, the economy, provided that the right cultural and policy environment is in place.29

So what will happen now that the great population boom of the last two centuries is waning? A first- order effect is a slowdown in the size of the global workforce. The world’s working-age population (15–64) grew by 1.3 billion, or 40 percent, between 1990 and 2010.30 But this pace cannot continue, because the people who would be necessary to make that happen were quite literally never born. Due to the global decline in birth rates over the last two decades, the global working-age population will likely grow by only about 900 million between 2010 and 2030, or 400 million less than the previous two decades.31 Indeed, over the next forty years, the working-age population will shrink throughout Europe and East Asia (see Figure 5).32

For instance, the working-age population of Western Europe will shrink in absolute size even with continued high levels of immigration. Over the next twenty years, its pool of men and women age 15– 64 will fall by 4 percent even if Western Europe accepts 20 million new immigrants. Meanwhile, the population over 65 will likely grow by 40 percent.33 Coaxing more women out of the home and into the paid workforce, as is official European Union policy, would help to improve the dwindling ratio of workers to retirees, but at the risk of driving down birth rates still more. Raising the average age of retirement would also help arrest the declining size of the workforce, but here, too, there are clear political and practical limits. For example, despite all the talk of “70 being the new 60,” the health status of the next generation of seniors in the developed world is likely to be lower than that of their counterparts today. This is because of sharp increases in chronic conditions among today’s late-middle-agers, due to the global obesity epidemic and other factors.34

In Europe and East Asia, the decline in the numbers of younger workers will be even sharper than the decline in older workers, with consequences that could be particularly grave for economic dynamism. In every country of the world, regardless of its stage of economic development, form of government, or age structure, the highest rates of entrepreneurial activity are found among those age 25–34—an age group whose numbers will be shrinking in many advanced countries (see Figure 6).35

To be sure, during the early stages of fertility decline, nations often experience prosperity, a phenomenon known as the “demographic dividend.” As birth rates first turn down, a rising share of workers occupy the prime productive years of young adulthood. With fewer children around to support and care for, vast reserves of female labor are freed up to join the market economy, and adults are free to devote more money to savings, consumer durables, and real estate. Societies traversing through this early stage of population aging often find they have more resources available to invest in each remaining child, so their literacy rates, for example, improve. This phenomenon clearly happened in Japan and the other “Asian Tigers” from the 1960s to the 1990s and is still at work in China today.36

But with the next generational turn, the “demographic dividend” has to be repaid. So long as birth rates remain low, there are still comparatively few children, but the proportion of productive younger workers now begins to decline even as the ranks of risk-averse, middle-aged citizens and dependent elders explodes. Population aging goes from being a positive force for economic development and innovation to being a drain on resources—as is already happening now in Japan, which is now struggling to pay for the rising costs of its public pensions as its working-age population shrinks and its elderly population surges.37 This will be the story of China over the next forty years, as Figure 5 indicates. China’s working-age population will begin falling by 1 percent a year after 2016—with its population of people in their twenties and thirties specifically in even steeper decline.38 Meanwhile, the population of Chinese seniors (age 65 and over) will swell from 109 million, or 8.2 percent of the population, to 279 million, or 20 percent of the population, by 2035.39 Chinese demographers now speak of the emergence of a 4-2-1 society, in which a single child becomes responsible for two parents and four grandparents. This sets up China to experience an even worse aging crisis than Japan is undergoing.

Finally, the global retreat from marriage is also likely to depress and distort economic growth. Evidence drawn from Europe and North America indicates that children who are raised in an intact, married home are more likely to excel in school and be active in the labor force as young adults, compared to children raised in nonintact homes.40 Married adult males also work harder than their unmarried counterparts and enjoy an income premium over single men of between 10 and 24 percent, in countries ranging from Germany to Israel to Mexico to the United States.41 These findings suggest that market economies in the Americas and Europe—from Canada to Chile, from Spain to Sweden—that are now experiencing a retreat from marriage will also reap a new crop of problems as fewer children have the opportunity to acquire the human and social capital they need to thrive in the global economy and as fewer men have the motivation that marriage brings to fully engage the world of work.

THE WELFARE STATE IN AN AGING SOCIETY

The financing of the welfare state also depends critically on population growth and strong families, as evidenced by the painful rollback of social programs in aging Europe and its sovereign debt crisis as well as Japan’s deepening debt problems. Indeed, a recent report by Morgan Stanley suggests that a country’s proportion of old people may now be a more important indicator of its likelihood of default than the size of its current debt, especially because older voters are not likely to support reforms in public pensions that limit their income.42

The demographic sources of the current crisis in the welfare state are not hard to fathom. So long as population is growing, each new generation of retirees can get back far more in public pensions and health-care benefits than they ever paid in without creating any financial encumbrance on the future. But in the face of today’s population aging, old-age benefits can no longer be financed by a rapidly expanding labor force. They must instead be limited to what a shrinking working-age population is able and willing to contribute to the elderly’s support.

France, Germany, Sweden, Italy, Japan, and many other aging countries have already made draconian cuts in their promised of future pensions, even as insolvency or threat thereof is forcing many others (such as Greece, Spain, and Ireland) toward the same course.43 Even the United States is now coming to grips with a similar problem; for instance, in 2010 Social Security began paying out more to the elderly than it is taking in from current workers.44 In an aging society, growing expenditures for pensions and health care for the elderly also inevitably compete with the resources available to invest in children and families. Faced with a mounting budget deficit, the United Kingdom has cut child benefits while largely protecting pensioners.45 Thus, fertility declines and growth in aging populations pose a fundamental challenge to the financial viability of the welfare state in much of the developed world.

APPROPRIATE FAMILY POLICY IN AN AGING SOCIETY

What then are the appropriate policy responses to the unsustainable state of family life in many advanced societies? Here are ten proposals that might be helpful:

1. PROMOTE FAMILY ENTERPRISE.

The last generation has seen a rapid increase in corporate consolidation. Whereas rigorous enforcement of antitrust and other policies preserved an important role for small-scale family farms and businesses until the 1980s, today there is almost no check on the growth of giant retailers, agribusinesses, and industrial concerns. As British social theorist Philip Blond has written, “Our fishmongers, butchers, and bakers are driven out—converting a whole class of owner occupiers into low wage earners, employed by supermarkets.”46 Though it is not possible, or even desirable, to entirely reverse these trends toward monopolization, it is possible to moderate them and thereby carve out more space for family enterprise and entrepreneurship, which will in turn help to rebuild the economic foundation of the family. A good start would be to offer payroll tax breaks to small businesses and to more rigorously enforce existing antitrust laws.

2. INCREASE INCOME SECURITY FOR YOUNG COUPLES.

Young couples contemplating starting a family now face far greater risk than their parents typically did that they will face repeated spells of un- and underemployment. As political scientist Jacob Hacker has demonstrated, even before the Great Recession of 2008, the size of swings in pretax family income from year to year had doubled in the United States since the early 1970s.47 In Europe, many young adults typically find themselves maneuvering from contract to contract, rather than being able to settle into a secure career that will support a family. In the developing world, young adults often find themselves trying to get ahead amid the swirl of hypercompetitive megacities that seem to have literally no room for children.

There is no single policy lever to pull that will put the family back into a healthy and sustainable balance with global market forces. We must grapple with issues like foreign trade, offshore employment, and downsizing. Yet it is essential that measures of efficiency not be so narrowly defined that they discount the vital role that secure, functioning families play in sustaining economic progress. To soften the blows young adults face from income and employment instability associated with globalization, countries should ensure access to affordable health care and lifetime learning to keep job skills from becoming obsolete.

3. EASE THE TENSION BETWEEN HIGHER EDUCATION AND FAMILY FORMATION.

A woman’s education strongly predicts how many children she will have. For American women age 40– 44 in 2008, the average number of children among those with advanced degrees was just 1.6, compared to 2.4 for those who never graduated from high school. Fully 21.5 percent of highly educated woman remain childless throughout their lives, compared to only 15 percent of high-school dropouts.48

To some extent, these disparities simply reflect differing individual priorities and preferences. They also reflect, however, the severe obstacles placed in the way of couples who want to start families while they are still biologically capable of doing so and at the same time want to pursue higher education. Under our current system of higher education, a woman who wants to, say, interrupt her education at age 20 to start a family and then return to school at age 30 will face steep handicaps in gaining admission. Institutions of higher learning, as well as employers, should include parents in their attempts to build diversity and overcome historical patterns of discrimination.49

4. BUILD LIVABLE, FAMILY-FRIENDLY COMMUNITIES.

Around the world, high-cost housing is closely associated with low birth rates. This is particularly true in Japan, South Korea, Europe, and coastal China.50 Though housing is comparatively affordable in most parts of the United States, deteriorating public schools in many areas force parents into bidding wars for homes in good school districts or compel them to pay for private school or limit their family size. At the same time, underinvestment in transportation—particularly efficient, affordable mass transit—is forcing parents in many parts of the United States and Canada to endure long commutes that have a negative financial and emotional impact on family life.51 Suburbia, once a fount of fertility, needs to be refitted and modernized to make it family friendly again.

The policy responses needed to address these threats to the family are much easier to state than to achieve. Yet such vital reforms as improving public education, reducing automobile dependency, and fostering walkable communities will perhaps be easier if these goals are tied to the needs of the family. Salt Lake City, which has the highest birth rate of any American metropolitan area, has since the late 1990s made a huge and successful commitment to containing sprawl and building light-rail under the influence of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints.52

5. HONOR WORK-FAMILY IDEALS OF ALL WOMEN.

Women are diverse in their life preferences, no less so when it comes to the balance of motherhood and career than in any other realm. For example, in the United States, about one-fifth of married mothers state that their ideal preference is to remain in full-time employment; almost half prefer to work part-time only, and a full one-third prefer to avoid working outside the home while they raise children.53 Though the proportions of women expressing preference for one of these three broad options varies over time and among countries, research shows that the ratios are remarkably consistent. In general in developed nations, about 20 percent of women favor a home-centered life, 60 percent prefer a life that combines career and family, and about 20 percent are primarily concerned with career only.54

Unfortunately, government family policy often ignores this diversity among women. Instead, there is often bias toward the needs of working mothers and neglect of those of home-centered mothers. Pronatalist policies are not likely to be effective if they primarily target career-oriented women; such women are not only a minority in any national population but are generally the most resistant to increased childbearing. As sociologist Catherine Hakim points out, family policy that is aimed only at the particular problems of two-paycheck families fails “to recognize and accept the heterogeneity of women’s (and men’s) lifestyle preferences.”55

Policy makers should embrace programs such as the highly successful Finnish homecare allowance, which provides parents who do not use public childcare with a stipend that they can use for their own family budget—or to pay a grandparent, neighbor, friend, or nanny to care for their children. In Finland, the allowance is less expensive than the cost of public childcare and is linked to increases in fertility.56 Most importantly, it has allowed women to choose the best caregiving option for themselves and their families.

6. SUPPORT MARRIAGE AND RESPONSIBLE PARENTHOOD.

There are limits to what any government can or should do to promote marriage as an institution. Nonetheless, public policy should stop penalizing marriage and should also support initiatives to educate the public about the benefits of marriage and the hazards of single parenthood. This is no different in kind from government efforts to educate the public about the benefits of properly installed car seats for children or the hazards of smoking.

First, many public policies unintentionally penalize marriage by reducing or eliminating public benefits to parents who marry and thereby have access to two incomes rather than one.57 Public policies aimed at families should either be offered on a universal basis or should allow the two parents to split their income when it comes to determining the family’s eligibility for public support.

Second, governments should test the effectiveness of social-marketing campaigns on behalf of marriage— especially those connecting marriage and parenthood. Experience has shown that well-designed social- marketing campaigns aimed at changing sexual behavior, drug use, and smoking habits can have a positive impact.58 In some cases, the impact of these campaigns has proved to be modest. Yet the extraordinary cost, both to individuals and society, of contending with, for example, out-of-wedlock births, makes social marketing aimed at changing such behaviors likely to be cost effective. These campaigns can also generate a larger, salutary conversation in the society at large about the importance of marriage for raising children.

7. PROMOTE THRIFT.

Young adults in today’s developed countries, and increasingly in developing nations as well, are encumbered by debt to an unprecedented degree. According to the Project On Student Debt, the average American college graduate in the class of 2009 faces $24,000 in student loans, a figure that has risen by 6 percent every year since 2003.59 Mountains of credit-card debt also now typically encumber young couples contemplating whether to start a family; this is an obvious discouragement to fertility.

Better consumer-finance-protection laws and enforcement are part of the solution, from putting caps on usurious lending to enforcing standardized, easy-to-understand contracts for credit cards and mortgages. So is restoring the ethos of thrift that historically was a pillar of the thriving working- class and middle-class family. Until it petered out in the 1960s, Americans celebrated “Thrift Week” pegged to Benjamin Franklin’s birthday on January 17. Until the 1960s, public schools ran their own small banks for students, allowing millions of American children to better learn financial literacy and the habits of thrift. Savings and loans encouraged thrift through Christmas savings plans. And so on. We need to renew this ethos for our day. Restoring thrift is a generational project but also a prerequisite to restoring the health and fertility of the modern family.60

8. ADJUST THE FINANCING OF THE WELFARE STATE TO MEET THE NEEDS OF AN AGING SOCIETY.

All pension and health-care benefits, including those conveyed through the private sector, are ultimately financed by babies and those who raise and educate them. Yet in modern societies, the “nurturing sector” of the economy is starved for resources. Parents in particular rarely receive any material compensation for the sacrifices they make on behalf of their children.

Here is a suggestive policy idea for allowing the nurturing sector to keep a greater share of the value it creates for society: Say to the next generation of young adults, have one child, and your payroll taxes, which support the elderly, will drop by one-third. A second child would be worth a two-thirds reduction in payroll taxes. Have three or more children, and pay no payroll taxes until your youngest child turns 18. When it comes time to retire, your benefits (and your spouse’s) will be calculated just as if you had both been contributing the maximum tax during the period in which you were raising children, provided that all your children have graduated from high school.

9. CLEAN UP THE CULTURE.

Television and other global media, as we’ve already seen, appear to have played a big role in driving birth and marriage rates down. From pop stars’ efforts to push the sexual envelope, to Hollywood films, violent video games, and ubiquitous Internet pornography, the global media sends a strong message to young people around the world that a family-centered way of life is passé.

To some extent, these cultural excesses and distortion can be expected to correct themselves. Just as during the Victorian age, when fear of underpopulation, particularly among elites, led to a reformation in manners and morals, there will be less and less tolerance for those who do not contribute children to society or whose activities contribute to children’s moral corruption. But Hollywood film makers, advertisers, and other cultural merchants need to catch up with the new demographic reality and become aware that we now live in a world in which strong families can no longer be taken for granted—much less endlessly mocked and trivialized.

10. RESPECT THE ROLE OF RELIGION AS A PRONATAL FORCE.

Childlessness and small families are increasingly common among secularists. Meanwhile, in Europe and the Americas, as well as in Israel, the rest of the Middle East, and beyond, there is a strong correlation between adherence to orthodox Christian, Islamic, or Judaic religious values and larger, stable families.

In recognition of the contribution that religion makes to family life and fertility, governments should not persecute people of faith for holding or expressing views that are informed by religious tradition, including ones that buck progressive or nationalist sensibilities. Alas, such persecution is now common in some countries around the world, from Canada to China to France.61 Faith brings hope, and ultimately it is hope that replenishes the human race.

None of these ten proposals is anywhere near adequate to solve the challenges created by the new demographics of the twenty-first century. Yet they are suggestive of the philosophical approach that is needed—one that emphasizes the critical role of the intact, nurturing, and financially secure family in sustaining and renewing the human, social, and financial capital of aging societies around the globe.

Phillip Longman is a senior research fellow at the New America Foundation in Washington, D.C.; Paul Corcuera is a professor and investigator at Instituto de Ciencias para la Familia at Universidad de Piura (Peru); Laurie DeRose, Ph.D., is a research assistant professor in the Maryland Population Research Center at the University of Maryland, College Park; Marga Gonzalvo Cirac, Ph.D., is a professor and researcher at the Institut d’Estudis Superiors de la Familia (IESF) at the Universitat Internacional de Catalunya (Spain); Andres Salazar is a professor and investigator at Instituto de La Familia at Universidad de La Sabana (Colombia); Claudia Tarud Aravena is the director of the Family Science Institute at the University of the Andes (Chile); and Antonio Torralba is an associate professor, a university fellow, and trustee of the University of Asia and the Pacific (Philippines).

1 Population Division of the Department of Economic and Social Affairs of the United Nations Secretariat, World Population Prospects: The 2010 Revision (New York: United Nations, 2011): http://esa.un.org/unpd/wpp/index.htm.

2 Ibid.

3 Ibid.

4 Ibid.

5 Ibid.

6 Sheela Kennedy and Larry Bumpass, “Cohabitation and Children’s Living Arrangements: New Estimates from the United States,” Demographic Research 19 (2008): 1663–1692.

7 Shannon E. Cavanaugh and Aletha C. Huston, “Family Instability and Children’s Early Problem Behavior,” Social Forces 85 (2006): 551–581.

8 W. Bradford Wilcox, When Marriage Disappears: The New Middle America (Charlottesville, VA: The National Marriage Project, Institute for American Values, 2010).

9 Sheela Kennedy and Elizabeth Thomson, “Children’s Experiences of Family Disruption in Sweden: Differentials by Parent Education Over Three Decades,” Demographic Research 23 (2010): 479–508.

10 U.S. Census Bureau, Statistical Abstract of the United States: 2011 (Washington: U.S. Census), 840.

11 Paul R. Amato, “The Impact of Family Formation Change on the Cognitive, Social, and Emotional Well-being of the Next Generation,” Future of Children 15 (2005): 75–96; Camille Charles, Vincent Roscigno, and Kimberly Torres, “Racial Inequality and College Attendance: The Mediating Role of Parental Investments,” Social Science Research 36 (2007): 329–352; Elizabeth Marquardt, “Gift or Commodity: How Ought We to Think About Children?” (presented at Social Trends Institute experts meeting, “Whither the Child?” Barcelona, Spain, March 2010); W. Bradford Wilcox et al., Why Marriage Matters (New York: Institute for American Values, 2011).

12 Amato, “Impact of Family Formation Change.”

13 Gunilla Ringback Weitoft, Anders Hjern, Bengt Haglund, and Mans Rosen, “Mortality, Severe Morbidity, and Injury in Children Living with Single Parents in Sweden: A Population-based Study,” Lancet 361 (2003): 289–295.

14 Population Division of the Department of Economic and Social Affairs of the United Nations Secretariat, World Population Prospects: The 2008 Revision and World Urbanization Prospects: The 2009 Revision (New York: United Nations).

15 John C. Caldwell, Theory of Fertility Decline (New York: Academic Press, 1982).

16 Wolfgang Lutz, Stuart Basten, and Erich Striessnig, “The Future of Fertility” (presented at Social Trends Institute experts meeting, “Whither the Child?” Barcelona, Spain, March 2010).

17 Michele Boldrin, Mariacristina De Nardi, and Larry E. Jones, “Fertility and Social Security,” NBER Working Paper No. 11146 (2005).

18 Ron Lesthaeghe, “The Unfolding Story of the Second Demographic Transition” (presented at Social Trends Institute experts meeting, “Whither the Child?” Barcelona, Spain, March 2010).

19 Eric Kaufman, “Sacralization by Stealth? The Religious Consequences of Low Fertility in Europe” (presented at Social Trends Institute experts meeting, “Whither the Child?” Barcelona, Spain, March 2010).

20 Alicia Adsera, “Marital Fertility and Religion: Recent Changes in Spain,” IZA Discussion Paper 1399 (University of Chicago: Population Research Center, 2004).

21 Analysis of World Values Survey, 2005-2008; see also Alicia Adsera, “Fertility, Feminism and Faith: How are Secularism and Economic Conditions Influencing Fertility in the West?” (presented at Social Trends Institute experts meeting, “Whither the Child?” Barcelona, Spain, March 2010).

22 Janet S. Dunn, University of Michigan, “Mass Media and Individual Reproductive Behavior in Northeastern Brazil” (paper presented at the XXIV General Population Conference of the International Union for the Scientific Study of Population, August 18–24, 2001); Joseph E. Potter and Paula Miranda-Ribeiro, “Below Replacement Fertility in Brazil: Should We Have Seen it Coming?” (presented at Social Trends Institute experts meeting, “Whither the Child?” Barcelona, Spain, March 2010).

23 Ministry for Health, Welfare and Family Affairs, South Korea: http://english.mw.go.kr/front_eng/index.jsp.

24 See Table 1 and Table 2 in “International Family Indicators” section, below.

25 Mikko Myrskylä, Hans-Peter Kohler, and Francesco C. Billari, “Advances in Development Reverse Fertility Decline,” Nature 460 (2009): 741-743; Leonard Schoppa, “Feminism as the New Natalism: 21st Century Prescriptions for Addressing Low Fertility,” Social Trends Institute, “Whither the Child?” Experts Meeting (March, 2010); David Willetts, “Old Europe? Demographic Change and Pension Reform,” Centre for European Reform (2003): http://www.cer.org.uk/pdf/p475_pension.pdf.

26 Fumitaka Furuoka, “Looking for a J-shaped Development-fertility Relationship: Do Advances in Development Really Reverse Fertility Declines?” Economics Bulletin 29 (2009): 3067–3074.

27 In France, for example, more than a third of the officially estimated increase in the birth rate between 1997 and 2004 came from women of foreign nationality. See France Prioux, “Recent Demographic Developments in France: Fertility at a More Than 30-Year High,” Demographic Trends, Institut National d’Etude Démogaphiques (2007): http://www.ined.fr/en/publications/demographic_trends/bdd/publication/1345/.

28 Edward Crenshaw and Kristopher Robison, “Socio-demographic Determinants of Economic Growth: Age-Structure, Preindustrial Heritage and Sociolinguistic Integration,” Social Forces 88 (2010): 2217–2240.

29 Julian Simon, The Ultimate Resource (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1981).

30 Nicholas Eberstadt, “World Population Prospects and the Global Economic Outlook: The Shape of Things to Come,” The American Enterprise Institute, Working Paper Series on Development Policy 5 (2011).

31 U.S. Census Bureau International Data Base: http://www.census.gov/ipc/www/idb/informationGateway.php.

32 See also Eberstadt, “World Population Prospects.”

33 Ibid.

34 Marga Gonzalvo-Cirac, “El Descenso Irreversible de la Mortalidad en el Siglo XX en la Provincia de Tarragona. Analisis Demografico y Epidemiologico” (doctoral thesis, Universitat Internacional de Catalunya, Barcelona, Spain, 2011); Linda G. Martin et al., “Trends in Disability and Related Chronic Conditions Among People Ages Fifty to Sixty-Four,” Health Affairs 29 (2010): 725–731.

35 Niels Bosma and Jonathan Levie, Global Entrepreneurship Monitor: 2009 Annual Report (Babson Park, MA: Global Entrepreneurship Research Association, 2010), 24.

36 David E. Bloom et al., The Demographic Dividend: A New Perspective on the Economic Consequences of Population Change (Santa Monica, CA: Rand Corporation, 2003).

37 Ibid.

38 U.S. Census Bureau projection, cited by Eberstadt, “World Population Prospects,” 14.

39 Population Division of the Department of Economic and Social Affairs of the United Nations Secretariat, World Population Prospects: The 2010 Revision, medium variant.

40 See, for instance, Amato, “Impact of Family Formation Change”; John F. Ermisch and Marco Francesconi, “Family Structure and Children’s Achievements,” Journal of Population Economics 14 (2001): 249–270.

41 Avner Ahituv and Robert Lerman, “How Do Marital Status, Labor Supply, and Wage Rates Interact?” Demography 44 (2007): 623–647; Claudia Geist, “The Marriage Economy: Examining the Economic Impact and the Context of Marriage in Comparative Perspective” (doctoral thesis, University of Indiana, Bloomington, Indiana, 2008); Wilcox et al., Why Marriage Matters.

42 Arnaud Mares, “Ask Not Whether Governments Will Default, But How,” Sovereign Subjects (Morgan Stanley: August 25, 2010).

43 Richard Jackson, Neil Howe, and Keisuke Nakashima, The Global Aging Preparedness Index (Washington, DC: Center for Strategic and International Studies, 2010).

44 Social Security and Medicare Boards of Trustees, A Summary of The 2011 Annual Reports (Washington, DC: Social Security Administration, 2011).

45 Chris Giles, “Today’s Austerity is Tomorrow’s Indignation,” Financial Times (June 29, 2011): http://www.ft.com/cms/s/0/40be7044-a286-11e0-9760-00144feabdc0.html#axzz1SUZkiiEl.

46 Philip Blond, “Rise of the Red Tories,” Prospect (February 28, 2009): http://www.prospectmagazine.co.uk/2009/02/riseoftheredtories/.

47 Jacob S. Hacker, The Great Risk Shift (New York: Oxford University Press, 2006).

48 Jane Lawler Dye, “Fertility of American Women: 2006,” Current Population Reports, P20-563 (Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau, 2008), Table 2.

49 Phillip Longman and David Gray, “Family-Based Social Contract, New Social Contract Initiative,” New America Foundation (November 2008): http://workforce.newamerica.net/publications/policy/family_based_social_contract.

50 Lesthaeghe, “Unfolding Story”; Sidney B. Westley et al., Very Low Fertility in Asia (Honolulu, HI: East-West Center, 2010).

51 National Resources Defense Council, Reducing Foreclosures and Environmental Impacts through Location-Efficient Neighborhood Design (January 2010): http://www.nrdc.org/energy/files/LocationEfficiency4pgr.pdf.

52 Patrick Doherty and Christopher B. Leinberger, “The Next Real Estate Boom,” Washington Monthly (November/December 2010): http://www.washingtonmonthly.com/features/2010/1011.doherty-leinberger.html.

53 W. Bradford Wilcox and Jeffrey Dew, “No One Best Way: Work-Family Strategies, the Gendered Division of Parenting, and the Contemporary Marriages of Mothers and Fathers,” in W. Bradford Wilcox and Kathy Kovner Kline (eds.), Gender and Parenthood: Natural and Social Scientific Perspectives (New York: Columbia University Press, 2012).

54 Catherine Hakim, “What Do Women Really Want? Designing Family Policies for All Women” (presented at Social Trends Institute experts meeting, “Whither the Child?” Barcelona, Spain, March 2010), Table 1.

55 Ibid.

56 Ibid.

57 Adam Carasso and C. Eugene Steurle, “The Hefty Penalty on Marriage Facing Many Households with Children,” The Future of Children 15 (2005): 157–175.

58 G. Hastings, M. Stead, and M.L. McDermott, “The Meaning, Effectiveness and Future of Social Marketing,” Obesity Reviews 8 (2007): 189–193; Leslie B. Snyder et al., “A Meta-Analysis of the Effect of Mediated Health Communication Campaigns on Behavior Change in the United States,” Journal of Health Communication 9, supplement 1 (2004): 71–96.

59 Project on Student Debt, Student Debt and the Class of 2009 (Oakland, CA: Project on Student Debt, 2010): http://projectonstudentdebt.org/files/pub/classof2009.pdf.

60 For a history of the American thrift movement of the Progressive Era and for policy ideas for rekindling it, see Phillip Longman and Ray Boshara, The Next Progressive Movement: A Blueprint for Broad Prosperity (Sausalito, CA: Polipoint, 2008).

61 Pew Forum on Religion and Public Life, Rising Restrictions on Religion (Washington, DC: Pew Research Center).